Supported by:

A Nose for GC

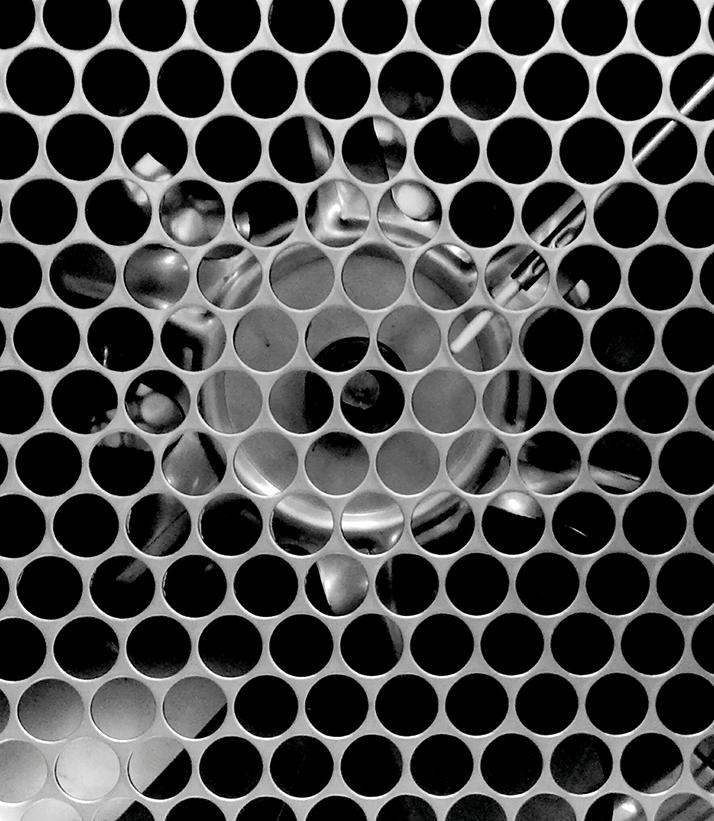

We’ve shown that trained dogs can detect the presence of malignant ovarian cancer tumors using smell. The dogs use odor cues to distinguish blood samples of patients with ovarian cancer from those of healthy women, and even from those with benign ovarian tumors. This is an inside look at the gas chromatography-olfactometry (GC-O) instrument we are using to identify the specific volatile organic chemical biomarkers that the dogs are detecting. Submitted by Katharine Prigge, Monell Center, US. Photo: Nicole Greenbaum

Blossoming Bioassays

Paper is patterned using a craft punch to form a flower-like shape. Every petal is an independent detection zone. Orange petals are for detecting glucose. Through such simple geometry, segmented and multiplex immunoassay for HCV diagnosis could be carried out in an integrated, economic and rapid manner. Photo: Xuan Mu

Counting Cancer Cells

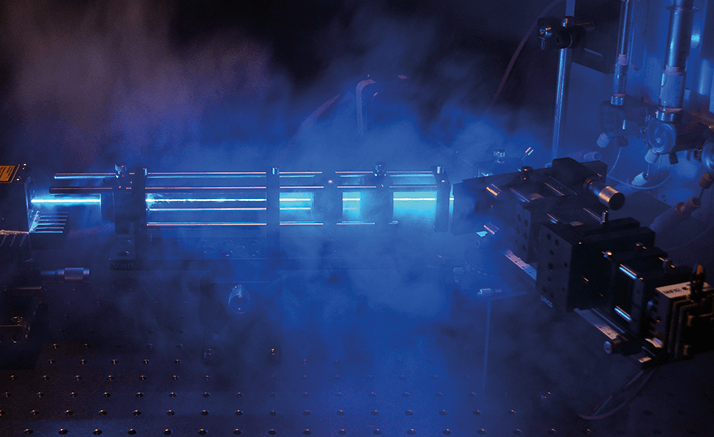

The PoCyton device developed by researchers at the micro-engineering branch of the Fraunhofer Institute for Chemical Technology in Mainz (IMM) is a cost-effective, small, and automated flow cytometer. Michael Baßler, research scientist at ICT-IMM, says, “Our flow cytometer enables [tumor cell quantitation] to be carried out around twenty times faster [than current technology]. Their cost is also lower by several magnitudes, which takes us into a new dimension that makes these devices much more affordable for clinical applications.” Photo: © Fraunhofer ICT-IMM

Designing Nano-Potteries

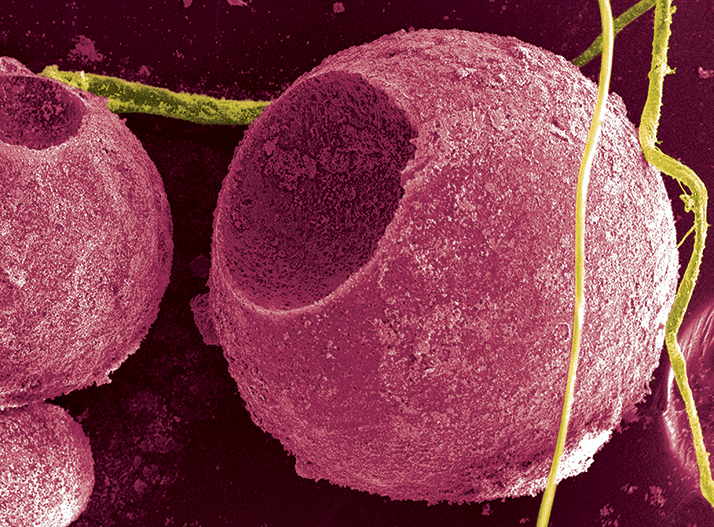

Imaging bio-molecules and cells over extended periods of time is critical to understanding cellular processes. The photostability of cadmium sulfide quantum dots are highly attractive for the real-time tracking of bio-molecules and cells over time. Pacific Northwest National Laboratory researcher Dev Chatterjee provided the image. Other contributors include Matthew Edwards, Paul MacFarlan, Samuel Bryan and Jason Hoki. Image colored by PNNL graphic designer Jeff London.Photo: Pacific Northwest National Laboratory

Makes Sense

Sheet of printed, disposable biosensor devices for a wearable, wirelessly-enabled sweat analytics platform. Photo: Electrozyme LLC

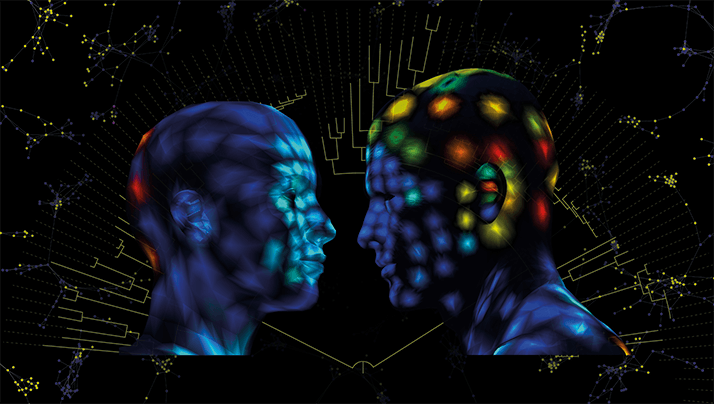

Skin Deep Analysis

Artistic representation of 3D mapping of the chemistry and microbes of the human skin. Each of the two renderings shows distribution of yet unknown molecules on the skin of either the female or male individual. Bouslimani et al., PNAS, 112 (17), E2120–E2129 (2014). Image: Theodore Alexandrov

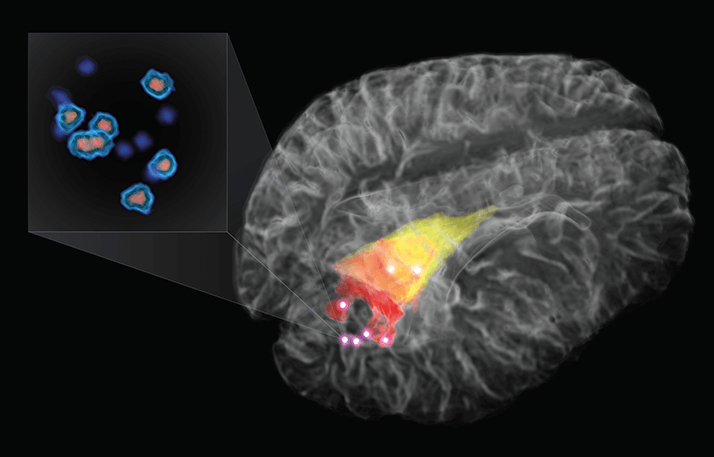

Multimodal Brain Probe

Post-surgery residual cancer cells are the primary cause of brain cancer recurrence, and result in a poor prognosis for patients. The image depicts a 3D rendering of the brain for a patient with brain cancer (glioma), with the cancer detectable on T1- and T2-weighted MRI in red and yellow respectively. The bright points indicate cancer detected using Raman spectroscopy, as far as 1 cm beyond what is detectable using MRI. The actual cancer cells are depicted in the pop out (based on histology images). By detecting invasive cancer cells, the surgeon should be able to conduct a more complete resection and thereby improve patient survival. M. Jermyn et al., Science Translational Medicine, 7 (274) 274ra19 (2015). Image: Michael Jermyn, Kevin Petrecca and Frederic Leblond

Needleless Blood Sugar

EMPA and the University Hospital Zurich have joined forces to develop a sensor that measures blood sugar through skin contact – and without calibration. “Glucolight” will initially to be used in premature babies to avoid hypoglycemia and subsequent brain damage. Photo: EMPA (www.empa.ch)Click the links below for more When Art Meets Science: Where Art Meets Science In Our Environment In Our Food Out of this World